Chapter 1

A Brief History of the Cell

The earliest observations of cells were made in the late seventeenth century, but their fundamental importance in the natural world only became apparent over 150 years later, in the middle of the nineteenth century. Since then, increasingly rapid strides have been taken toward understanding what goes on inside cells—and how such processes relate to growth, reproduction, inheritance, disease, and the origin of life on Earth.

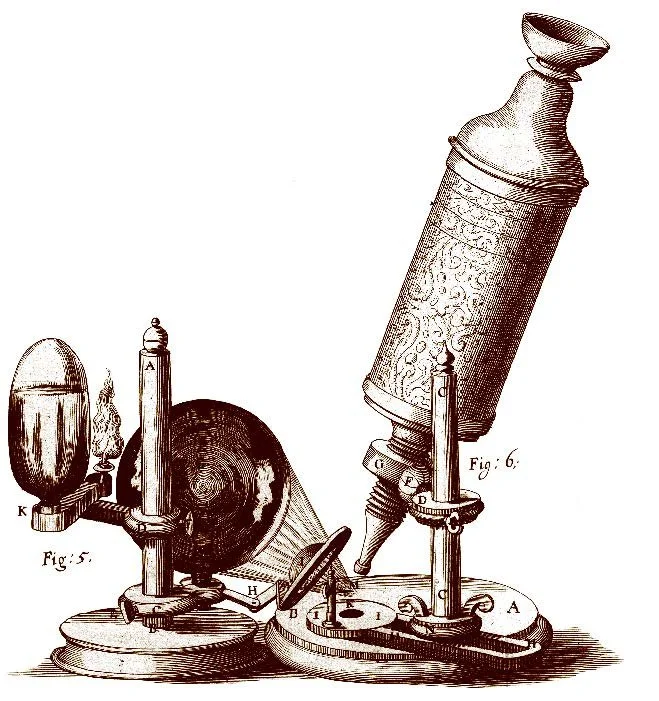

The most influential microscopist of the age was Englishman Robert Hooke. While employed as “curator of experiments” at the new Royal Society in London, Hooke made many observations through microscopes and telescopes, and produced a beautifully illustrated book of what he had seen. Micrographia was published in September 1665 and its exquisite drawings and intriguing text gave readers an insight into a world hidden from everyday eyes. The now famous diarist Samuel Pepys was among those captivated, noting: “Before I went to bed, I sat up till 2 a-clock in my chamber, reading of Mr. Hooke’s Microscopical Observations, the most ingenious book that I ever read in my life.”

It was Hooke who coined the word ‘cell’ to describe what he saw when studying cork. He placed thin slivers of the material onto a dark plate beneath his microscope’s objective lens, illuminated them with light from an oil lamp focused through a thick lens, and gazed through the eyepiece. His description of what he saw, quoted below, is still intriguing.

Leeuwenhoek was prolific; he made more than 500 microscopes and wrote hundreds of letters informing scientific societies about his discoveries— including 190 or so to the Royal Society in London. The drawings (left) are taken from one of his letters.

In 1675, Leeuwenhoek observed tiny living creatures in a sample of rainwater that had been standing for a few days. These microorganisms were far, far smaller than any living things anyone had ever seen. Leeuwenhoek called them “animalcules.” For the next year he studied river water, well water, and seawater, some of which he left standing for several days or weeks. Mostly, he saw protozoa and single-celled algae, which are about the same size as Hooke’s cork cells—some quite a lot larger. But in April 1676 he saw animalcules that were much smaller, and these he described as being so tiny that you would need to lay more than a hundred end to end to measure the same as a grain of sand. This was almost certainly the first observation of bacteria.

In the 1820s French botanist Henri Dutrochet boiled plant tissue in nitric acid to dissolve away the material that held the cells together. He watched as the cells separated into countless individual, self-contained “globules,” concluding that cells make up “the fruits, the stems, roots, leaves and flowers on all the plants on the surface of the planet.”

The German botanist Franz Meyen reached a similar conclusion in 1830, observing: “Plant cells occur either singly, so that each forms an individual, as in the case of some algae … or they are united together to form greater or smaller masses, to constitute a more highly organized plant.”

Drawings of plant cells by Henri Dutrochet, 1824.

In 1831 British botanist Robert Brown gave it a name: the “nucleus.” In the 1830s, another German botanist, Matthias Schleiden, suggested that nuclei were the source of new cells after he supposedly saw new cells forming around nuclei and then emerging from inside the cell. In 1837, Schleiden described what he had seen to his colleague, the zoologist Theodor Schwann, who recognized the description of the dark spots as something he had seen in the cells of tadpoles. Schwann was convinced that in animals, too, nuclei seemed to give rise to new cells.

The pencil sketch of the DNA double helix by Francis Crick.

In 1839, Matthias Schleiden, a German botanist, and Theodor Schwann, a German zoologist, independently proposed the cell theory. They stated that all living organisms, whether plants or animals, are composed of cells, and that the cell is the basic unit of life. This theory revolutionized our understanding of biology and laid the foundation for modern cell biology.

In 1879, Walther Flemming, a German biologist, observed the process of cell division (mitosis) in animal cells for the first time, providing insight into how cells reproduce and pass genetic information to their offspring.

In 1953, London, two molecular biologists, Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins, used a technique called X-ray crystallography to work out the relative positions of the atoms present in DNA. In Cambridge, James Watson and Francis Crick used the X-ray crystallography data to build a model of the DNA molecule made of hundreds of metal plates that represented the sugars, phosphates, and nucleobases. Watson and Crick’s model revealed the fact that DNA must have a double-helix structure—something like a twisted rope ladder.

Early observations of meiosis during the production of sperm cells in the worm. Drawings in The Text-book of Embryology by Fredrick Bailey and Adam Miller, first published in 1909.